Where was the Birka of Ansgar located?

Summary

This article will discuss the location of the marketcenter called Birka in ancient Nordic sources. It will build mainly upon the work of Adamus Bremensis, Adam of Bremen, in his history of the archbishopery Hamburg-Bremen (Gesta Hammaburgensis Ecclesiae Pontificum, [Ref.11], [Ref.12] and [Ref.57]) and the descriptions made herein about ancient Sweden from the time of Ansgar, and the references to Birka.

Using this work and other significant ancient sources that are relevant for a discussion of Birka, such as Snorri Sturluson's Heimskringla, [Ref.50] and [Ref.65], and the work of Rimbert, Ansgars succesor - Vita Ansgari, the life of Anskar [Ref.68], this article will execute an analysis upon the question of geographical localization of the two, at least in time, different places in ancient Sweden named Birka. Finally, this will be set in comparison with recent research regarding the topic and the used sources.

As background reading, this article serie provides A commented summary of Adam of Bremen, on page 140.

(Go to content list.)

(Return to main article.)

(Return to home page.)

Content

Where was the Birka of Ansgar located?

- Summary

- Content

- Introduction

- The need for objectivity

- The validity of Adam of Bremen

- Historical usage of Adams Gesta

- Lack of objectivity in references to Adam

- The purpose of Adams work

- The validity of Adams account for ancient Sweden

- The preserved transcriptions of Adams work

- The sources used by Adam

- Adams view of ancient Sweden

- Establishing a common understanding of `Birka'

- The meaning of Birka

- Possible interpretations of Birka

- The name `Birka'

- Notes on the meaning of `Birka'

- The term `Bjärköarätt'

- The swedish Nationalencyklopedia on `Bjärköarätt'

- Svenska Akademiens ordbok on `Bjärköarätt'

- Svenska landskapslagar on `Bjärköarätt'

- Geograhical references to a location named like Birka

- Discussion on a common understanding of `Birka'

- Questioning the origin for the term `Bjärköarätt'

- Questioning Stockholm as the master for Lödöse `Bjärköarätt'

- Notes on establishing a common understanding of `Birka'

- Discussion summary

- Placing Ansgars Birka in ancient Sweden

- The Birka of Ansgar

- The time aspect in Adams different accounts of Birka

- Geographical references to the Birka of Ansgar

- Discussion on placing the Birka of Ansgar in ancient Sweden

- Notes on placing Ansgars Birka

- TBD

- Further analysis

- Conclusions

- Article references

- Litterature and background articles

- Background articles

- Litterature

- External links

- Article revision history

(Return to top of page.)

Introduction

There can be little questions raised as to whether an actual location known as Birka was actually (or, rather, known to have been) located at the island Björkön in the lake Mälaren around the time when Adam of Bremen (1060 - 1075) wrote his work. This was well known at the time, and so was the town Sigtuna founded around 1000 AD by Olof Skötkonung.

However, the archeological findings at these locations up to the 11th century (the days of Adam) do not in any way serve as a garantuee that the same locations were at question in earlier references to a trading center named Birka, and especially the Birka referenced by the missionary Ansgar (Anskar, Oscar), about two hundred years (829 - 845 AD) before the days of Adam of Bremen.

This article will strive to raise some interest for the questions regarding one specific topic related to the work of Adam - the question of which trade center Ansgar visited in the mid 800s, or rather - where this town called Birka was located.

Purpose:

By applying a more strict, and most importantly unbiased and objective, view as to where the trading center of Ansgars Birka was located, this article reviews related sources and other known materials to present a hypothesis on the matter of finding Ansgars Birka, located somewhere in ancient Sweden.

Question:

Hypothesis:

- Ansgar came to the trading center Köpingsvik,which lies in the province of Öland, an island by Adam known to be called Holm.

- In the days of Adam, Birka at Björkön is found in ruins. At the time for the later (possible) designation of Köpingsvik to hold an archbishop seat in the Nordic territories (in the early 13th century), also the trade center in Köpingsvik is laid in ruins. This might be interpreted as a misunderstanding on the different references to Birka - in the days of Ansgar, and in the days of Adam.

- Following this hypothesis, the geographical references made by Adam for most parts will be shown to comply as an appropriate definition of Ansgars Birka located in Köpingsvik.

(Return to content list.)

The need for objectivity

As briefly discussed below, Lack of objectivity in references to Adam, on page 68, different opinions are upheld for explaining and depicting the history of ancient Sweden. The two sides are, by this author, denoted the Svealand and the Götaland theories.

Thus, it seems that either sides are declined to advocate those aspects of ancient Nordic sources, remains and other findings that serves the purpose of emphasizing the arguments of the supported theory.

It is, therefore, the intention of this article to compare these arguments and to investigate the geographical bearings that can be extracted from ancient sources.

(Return to content list.)

The validity of Adam of Bremen

In the very well worked through translation of Adams Gesta... in [Ref. 2], the authors Svenberg et.al. presents some interesting views on how to interpret the work of Adam, both in extensive comments on the text and in four complementary articles. Furthermore, Henrik Janson in his dissertation [Ref.32] elaborates on the topic of Adams underlying purposes, and has shown a most interesting background for the compilation of Adams Gesta, with a political influence and purpose guiding the author in his efforts to describe the history of Hamburg-Bremen1. In some aspects, this most definately affects also the geographical references made by Adam, mainly in the fourth book which is called A description of the islands in the northern ocean.

(Return to content list.)

Historical usage of Adams Gesta

Over the years, much trust have been laid upon Adams account, and it has been taken as a valid foundation for analysing the places described and finding their true locations, and existence. Amongst middleage historians, Adam of Bremen holds a prominent place. Some of his accounts have been used in almost all of the Nordic history writings since2.

It is thus not unlikely that both Snorri Sturlusson (e.g. in [Ref.50], [Ref.65]) and Saxo Grammaticus ([Ref.26]) were well aquainted with the work of Adam for their own writings on ancient Nordic myths, sagas and history.

Nowadays, however, counting for the last two decades, i.e. from about 1980 and onwards, a more profound view of Adams Gesta has come into vision. In this tradition, Adams Gesta can no longer be held as an altogether valid source of reference for ancient Nordic customs and traditions. One well supported view on this is given by Henrik Janson in his dissertation, which he has provided an online summary for in [Ref.59].

(Return to content list.)

Lack of objectivity in references to Adam

To the findings of the author of this article, much of the interpretations of Adams Gesta - as well as towards other contemporary sources - are very subjective in that a certain pre-made belief is guiding the interpretations made from findings in ancient sources or remains.

(Return to content list.)

The Svealand theory

For instance and relevant for this article, amongst most scholars it is a commonly held belief from the start that not only the thoroughly excavated trade center Birka at Björkön - well known around the lake Mälaren in the mid 11th century - but also the Birka of Ansgar, both were located at Björkön. This deduction, ackording to this author, is made mainly upon extrapolation backwards of known facts from the 11th century and onwards towards modern time.

Having a thus biased view, the interpretations made e.g. in [Ref. 2] by Svenberg et.al. and in other authors work that references Adam - quite frankly since the 13th century - are made in a way to serve the purpose of backing up that pre-made assumption, namely that both (in time differing) places referred to as Birka was one and the same.

This view, referred to by the author as the Svealand theory, uses as a matter-of-fact foundation that not only Ansgars Birka, but also the ancient Ubsola, the seat of the Sueonic kings, were located near Mälaren, and/or in the province of Uppland.

Ubsola then, more specifically is assumed to be either Gamla Uppsala (the place of the great kings mounds), or Uppsala (former called Östra Aros, East Aros), both (either of them) supposed to be hosting the ancient heathen Asa temple and the seat of Sueonic kings.

(Return to content list.)

The Götaland theory

An intense opposing interest from mostly non-scholars (e.g. Carl-Otto Fast [Ref.22], [Ref.23] and Holger Bengtsson [Ref.13] and Mac Key [Ref.35] ), and in later years also by some accredited scholars (to whom might be included Verner Lindblom in [Ref.40]), have long tried to present indications, and evidence, against the conclusions drawn by the Svealand theory. For the mentioned authors this have been an essential part in their respective works, striving to place the ancient Ubsola not in Uppland, but in the county of Västergötland. Other conclusions may also be found, by both non-scholars and scholars, finding locations in other parts of Götaland. This theory, then, might be called the Götaland theory. The other, and perhaps most significant interest of these mentioned authors, have been to challenge the foundations for the Svealand theory.

The original advocateours for the Götaland theory or Västgötaskolan3 are willing to seek evidence for Västergötland, and the lake Väner region in particular, to be the origin of both the different people called Sveas, Danes and Goths/Geats/Götar, and furthermore the location of all ancient myths, including Odin's Sithun (Sigtuna), Valhall, the ashtree Yggdrasil etc. and myths of e.g. Helge Hundingsbane and Sigurd Fafnersbane.

This also, in the opinion of this author, is very much colored by as much wishes and hopes as is the Svealand theory, in that both sides tend to overlook especially those findings that might support an alternative explanation, in favor of the ones held by their, respectively, preferred theory.

It can be added, that no certain circumstances have been shown to back up this assumptions made in the Götaland theory, although in some aspects there are substantial material that might be of interest for a more thorough investigation. Several accounts for the value in these hypothesis, by this author referred to as the Götaland theory, have been made by ackredited scholars. A most thorough work is the dissertation of Lars Gahrn in [Ref.24], ackompanied by a later set of articles in [Ref.24] which contains both a review of the "Götaland hypothesis", as well as a thorough discussion of available ancient sources and later research of these sources. Garhn has also written a summary article, in [Ref.89], which states his view of the Götaland theory. A more objective account is given by Henrik Janson, Till frågan om Svearikets vagga, [Ref.33].

(Return to content list.)

The purpose of Adams work

As for the work of Adam, I quote Anders Pilz4 in [Ref.11]:

- "Gesta Hammaburgensis ecclesiae pontificum är, litterärt sett, ett välskrivet och njutbart verk. Författarens intentioner överensstämmer väl med den uppnådda effekten i de avseenden som här har undersökts. Hans mödor vid hantverkets utförande är inte iögonenfallande. Adam har varit vuxen sitt ämne."

Gesta... is, litterary speaking, a well written and enjoyable work. The intentions of the author well corresponds to the desired effect [...].

It stands clear that Adam has had a definite purpose of his work, and that was to praise and commend the archbishopery of Hamburg-Bremen5, in a time when its bishop Adalbert were desperatley trying to aquire, again, political influence in the east-Frankish (German) empire6. It also seems clear that Hamburg-Bremen, in essence, were not really an archbishopery, at least not in respect of German catholic church (see Hamburg-Bremen claims as archbishop seat, on page 143).

To achive this underlying goal of the work, it was important for Adam to show that the archbishopery had continuously since the days of Ansgar two hundred years before, worked hard for missionary amongst the heathen, barbarian7,tribes of northern Europe. Northern Europe, of course, originally included not only Scandinavia but also the eastern parts of Europe, in todays Poland and Baltic states around the Baltic Sea.

(Return to content list.)

The validity of Adams account for ancient Sweden

To estimate the validity for the accounts that Adam gives of ancient Sweden, not only his underlying purposes most be considered. Also, the preserved copies of handwritten and printed transcriptions are somewhat diversed in that specific details vary between transcriptions. Furthermore, the sources that Adam himself have used must be considered and valued in the light of all these aspects.

This validity is discussed in further detail in the article A commented summary of Adam of Bremen.

(Return to content list.)

The preserved transcriptions of Adams work

In [Ref.11], a thorough description is made as for which written transcipts we have access to today8, discussed in more detail in The preserved transcriptions of Adams work, on page 144.

The A-sources are considered to be most coherent with Adams original text, out of which no transcripts are known.

(Return to content list.)

The sources used by Adam

It seems clear that Adam have used both written sources, and personal accounts from people with good or worse knowledge of Nordic whereabouts and conditions.

As for written sources, he seem to have used most available classic writings such as Tacitus, Vergilius etc. He also have had access to different history works, one of the most prominent (at least for the first books) being the Frankish history, written by Gregory of Tours [Ref.95].

Amongst his oral sources, he frequently holds the king of Danes, Sven Estridsson, as a valid and prominent source. Probably he have also have had the oppurtunity to meet some missionaries of his own time that have travelled to ancient Sweden, the land of the Sueones9, e.g. the bishops of Scania (Skåne). Another informer was probably his archbishop, Adalbert.

(Return to content list.)

Adams view of ancient Sweden

The land inhabited by the Sueones is by Adam referred to both as Sueonia, and sometimes as Suedia10. According to Nyberg11, Adam concieves of Suedia as a distinct, well-defined land, whereas Sueonia is a more floating description of the northern territories making up the modern state of Sweden.

In writings of class B, the term Suedia is most often exchanged by Sueonia. Nyberg suggests that this is due to the fact that class B copies of the handwritten work are mad ein Denmark, whereas A class are made in Germany. Thus, the Danish writers are assumed to be unfamiliar with the term `Suedia' and instead uses the other, `Sueonia'.

Another chief aspect of Adams work is his description of the heathen cult center Ubsola, normally translated as Uppsala. This is discussed in the article Where lies Ubsola - ancient Uppsala?.

(Return to content list.)

Establishing a common understanding of `Birka'

The name itself, Birka, is not entirely defined to be a distinct name of a place such as the island Björkö in lake Mälaren. As argued here by this author, it may well be a descriptive name for a generic trading center according to iron age and older middle age customs in Sweden and Scandinavia. Adding to this view does the existence of the trade law called `Bjärköarätt', that seemingly have been in use in both ancient Norway and Sweden.

(Return to content list.)

The meaning of Birka

Possible interpretations of Birka

In [Ref.69], Ryderup discusses several possible locations of the trade center Birka that Ansgar visited. A difference compared to most other treatments on the location of Birka (e.g. Gahrn, [Ref.24]) is that he also considers a trade center on Öland, namely Köpingsvik.

The main alternatives for localization of Birka are by Ryderup pictured to be Björkön, and Köpingsvik. As an ethymologic definition of `Birka', Ryderup refers the general discussion held about the meaning of Birka as follows:

- Functional name with a domestically derived meaning.

- Functional name with a foreignally derived meaning.

- Vegetational name.

- (1) "Grunden för ett inhemskt funktionsnamn är sammanhanget med björk. Schlyter ansåg under 1870- talet att Birka fått sitt namn efter biærk som var ett äldre ord för handel. Även den danska rättstermen birk återgår på detta. Han antar också att ortnamn som Björkö (Bjarkey) varit namn på handelsplatser i Norden. H. Hjärne ansåg i slutet av 1800- talet att det kunde ha varit björkstavar eller dyl. som användes till att inhägna platsen där marknaden hölls och jämför med att hasla vall. Vidare anser H. Hjärne att han i Ansgarii Vita har funnit en antydning genom det lövtält som där beskrivs. [...]"

- (2) "Kärnan för den utländska härledningen är friserna och deras handel. [...] Elis Wadsten skrev i Namn och Bygd [1914] att han ville härleda namnet birk från det frisiska berek eller bereg. Där betydelsen är rättskipning eller område där rättsskipning försiggår och som förekommer i medeltida källor från Brügge. Wadsten ansåg att berek hade en likadan betydelse som det danska birk som just betydde rättsdistrikt med egna lagar och egen domstol. [...]"

- (3) "Den vanligaste definitionen idag för Birka (Birca) är som ett vegetationsnamn, förmodligen en latiniserad form av Björkö. Det som E. Wessén hävdade redan 1923 och som avslutade den tidens debatt. Han ansåg det vara en yngre svensk form av det fornsvenska biærkö, som betyder "ö där björk växer". Vidare ansåg han att namnet på ön var äldre än handelsplatsen."

(1) Domestic functional names is founded upon birch, i.e. the tree. One interpretation (Schlyter) connects `birka' with biærk, an old word for trade12. This is found to comply with the danish rule of law term birk. Another interpretation (H.Hjärne) is that it refers to birch staffs used to enclose the grounds of the market[Note19].

(2) The foundation for foreignally lead derivation of Birka is the Frisian traders. One interpretation (Elis Wadsten) would be from Frisian berek or bereg, meaning a secluded area (jurisprudence) were administration of justice is held, linked to Brügge. Wadsten held that berek and the danish birk were the grounds for interpreting the meaning of `Birka'.

(3) Today, the most commonly held derivation is for Birka as a vegetational name, then probably latinized from Björkö - as stated by E Wessén in 1923, who considered Birka to be a younger form of biærkö, meaning "an island where birches grow". He also considered the name of the island (Björkö) to be older than the trade center.

(Return to content list.)

The name `Birka'

In Svenska Akademiens ordbok [Ref.70], the word Birka is described according to Birk och Birka, on page 113, defining the noun Birka and its confirmed uses.

BIRKA

Ethymology: Birk is identical to Biærkö, latinized as Birka, and the name used for several important trade related islands in Scandinavia, for which it has taken the meaning of trade center. Compare with the noun Birk (below).

Meaning: Trading village, trading town.

A reference is made from [Ref.99], calling the town Sigtuna a `Birka'.

BIRK

The word Birk used as a noun, in pluralis Birkar.

A reference is made from Nehrman, [Ref.106], stating that old towns used to be called market towns, although these as well as Birkar later were differented from proper towns.

(Return to content list.)

Notes on the meaning of `Birka'

(Return to content list.)

The term `Bjärköarätt'

Trading rights in the early middle ages was dictated by the so called `Bjärköarätt' law - possibly translated as the law of bjärk-islands13. This is referenced below from three sources.

The swedish Nationalencyklopedia on `Bjärköarätt'

In The swedish Nationalencyklopedia, [Ref.44], the term bjärköarätt is explained according to `Bjärköarätt', on page 114.

Bjärköa-right was the law that in older middle ages dictated life in the societies of Nordic towns and trade centers. No definitive derivation can be made of the name `bjärkö' or its origin. Suggestions are made from `Nbirk', secluded area, and birch, from the island Björkö where one known trade center was located.

The oldest known existences of `bjärköa'-laws were Norwegian, dated to the 12th and 13th centuries. A swedish `bjärköa'-law is preserved from 1345, and was used in Lödöse, province of Västergötland. Besides this only fragmentary pieces are found from the mid 14th century.

(Return to content list.)

Svenska Akademiens ordbok on `Bjärköarätt'

The section `Bjärköarätt', on page 114 also describes the related term `birkerätt' according to Svenska Akademiens ordbok [Ref.70].

The word bjärköarätt (birkerätt) is presented as the law for a given administrative area, such as a town or a trade center.

(Return to content list.)

Svenska landskapslagar on `Bjärköarätt'

Elias Wessén and Åke Holmbäck made a series of translations of ancient swedish provincial laws, in the serie Svenska landskapslagar14, [Ref.56]. This includes an extensively commented translation of the `Bjärköarätt' law, in [Ref.56-2], which is briefly referenced here.

The age of the `Bjärköarätt' law

The complete handwritings of the law is only preserved in one transcript, known as B58, in a collection with the younger Västgöta law now kept by Kungliga Biblioteket in Stockholm. This transcript can be stated as no older than 1345 AD, and probably - as held by Schlyter15 - written around 1350 AD. Besides the B58 transcripts, two fragmental transcripts have been found; the first - containing only the first three chapters - in a copy of the law of Södermanland; the third transcript have been found, in fragments, at the library of Vadstena monastery. Schlyter, [Ref.107], determined the two first transcripts as transcript A and B. The third, published by Liedgren, [Ref.103], is by him and Holmbäck & Wessén denoted transcript C.

It is stated in Svenska landskapslagar16 that the actual age of the law cannot be determined, but that it is considered to have been used as the town law for Stockholm prior to the Magnus Eriksson town law from the 14th century (see Viewing the Lödöse `Bjärköarätt' as a transcript originating from Stockholm, on page 75 below).

It is known to have been used in Lödöse, province of Västergötland - actually the only clearly referenced town in any of the transcripts, the B58 - and in one town in each one of the provinces of Södermanland (probably Nyköping) and Östergötland (probably Linköping or Skänninge). Holmbäck and Wessén concludes that the law was originally formed sometimes during the later part of the 13th century, though probably before the Uppland law in 1296 AD.

This they base upon the view of Stockholm as a predescessor for the Lödöse version of `Bjärköarätt', and the comparison with the Uppland province law from 1296 AD - which is found verbally and structurally much better written than the `Bjärköarätt' (hence, a later writing of the Bjärköarätt would show more textual alignments with the Uppland law). An existing town law for Stockholm that is older than the Magnus Eriksson town law - though not referenced by the name `Bjärköarätt' - is supported by two muniment documents from 1288 and 1297 AD, where a difference between town laws and province (or district) laws are indicated, though not clearly expressed17.

Viewing the Lödöse `Bjärköarätt' as a transcript originating from Stockholm

Holmbäck and Wessén mainly bases the assumption that the Lödöse version of `Bjärköarätt' originally was localized to Stockholm upon the mentioning of local geographical names significant for this town today, thus founding the interpretation of the B58 transcript for `Bjärköarätt' in Lödöse to be a `rip off' transcript of the Stockholm version (authors comment in [Note20]). It is hence their view that a straight replacement is assumed of the name Stockholm in favour of the name Lödöse. This interpretation is shared by their master translation made by Schlyter [Ref.107].

The geographical names are Kungshamn and Åsön, mentioned in chapter 13, and north and south Malmen, mentioned in chapter 39, which are interpreted as the harbor Kungshamn southeast of Stockholm, the geographical quarters of Stockholm Norrmalm and Södermalm, respectively the island Åsön where Södermalm of Stockholm is located.

A second important basis is in reference to Magnus Erikssons town law, section R 12:1. From this, Holmbäck and Wessén states that the below referenced text of chapter 13 is complemented by the specific amendment `Sama lagh haffwi alle andre städhi inrikes innan sin stadz mark'; translated: the same law prevails for all towns within our country.

A third argument by Holmbäck and Wessén is the mentioning in chapter 8, where Lödöse again is mentioned concerning trading rules for ships coming to the harbor. The term used is Lödöse travellers, for which a discussion is held as to whether it pertains to travellers coming to Lödöse, or travellers with origin in Lödöse (as opposed to travellers from other towns). This paragraph is also interesting because it mentions the trade of herring-fishing, a fish known as herring (sill)in the Western seas, but Baltic herring (strömming) in the Baltic sea, north of Skåne/Blekinge.

Other sources to `Bjärköarätt' besides the Lödöse transcript

From the declaration by king Magnus Eriksson in 1349, giving Jönköping the right to `utilize the regulations called byärkerätt in use in Stockholm'18, a transformation on the meaning of the term `bjärköarätt' is explained by the authors first as syllable for town right, then from the 15th century and onwards being connected to the trade center on Björkön, Mälaren19. This latter view is circumstanced by the 15th century discovery of the Ansgar legend - which was not known when the law was first transcribed. In later references, the law was to be called `Björkö rights', claiming this town to be the oldest in Sweden and therefore the origin of the law.

Holmbäck and Wessén actually follows this claim when they declare all other Nordic references of `Bjärköarätt' to be originating from Björkön, Mälaren, a proposed "fact" which is discussed in [Note21] below and more thoroughly in Questioning the origin for the term `Bjärköarätt', on page 77.

The oldest known appearance of the word itself - biarkeyiarréttr - exists from a deal between Olav the holy of Norway and the Icelandic people in 1020, confirmed in a testimony around 1080 being preserved in the icelandic lawbook Grågås20. Following this, the Norwegian version of the law seems first to have been written in the 12th century, out of which a transcript fragment is preserved from the first part of the 13th century. [Note22]

A version named biärkerät for the province of Skåne is, according to Holmbäck and Wessén, considered to have been written during the first part of the 13th century. Holmbäck and Wessén holds the view that a Danish lack of tradition for the original meaning of the word lead to a comprehension as `a right for a biärk', from which later arose the term birk, meaning `separate jurisprudence', that is, separated from the surrounding law of the province (or district).

They also, however, in a note references the opposing view of E. Wadstein21, who claims that the term is not connected to Björkö, but to a frisian term berek, meaning `independent jurisprudence'. On this view Holmbäck and Wessén remark that the Frisian term only is known in a couple of late mid-netherlandic sources which linguistically seem to be a late word construct, as is the Danish term birkeret. Wadstein, as related from Ryderup above (Possible interpretations of Birka, on page 72), claims that `Bjärköarätt' is the origin for the name Birca, since the town constitutes a birk - quite the contrary, then, to the view held by Holmbäck and Wessén that Björkö in Mälaren would be the origin of the term `bjärköarätt'.

The `Bjärköarätt' law is not the only known township law from early middleages. Holmbäck and Wessén mentions `Söderköpingsrätten' and `Visby stadslag', which most apparent difference from `Bjärköarätten' is that these towns, the first in the province of Södermanland, the other on the island Gotland, seem to make note of a German population, and especially the Visby township law is clearly influenced by German township laws22.

(Return to content list.)

Geograhical references to a location named like Birka

The most well-known connection of Birka and a geographical location in Scandinavia is, naturally, the one at the island Björkön in lake Mälaren, Sweden. This is however not at all the exclusive existence of such a geographical name.

As indicated from Other sources to `Bjärköarätt' besides the Lödöse transcript, on page 76, several other occurences of `Bjärköarätt' indicates a similar law, in similar trade centers and towns, at least from the 11th century.

(Return to content list.)

Discussion on a common understanding of `Birka'

Some interesting points for discussion are treated in this section, followed by the notes made in the chapter, Notes on establishing a common understanding of `Birka', on page 84.

Questioning the origin for the term `Bjärköarätt'

It does not seem logical that all sources referencing the term `Bjärköarätt', or a similar term, from ages older than the town Stockholm and located all over Scandinavia (even with Frisian connections) should have originated inside the 8th - 10th century trade center in Mälaren, at Björkön. That would require a very predominant role for this trade town, one which there are no clear evidence found for.

(Return to content list.)

Questioning Stockholm as the master for Lödöse `Bjärköarätt'

Discussion points

This discussion will be held unbiased by the view of Bjärköarätt connected to Stockholm - or any other `mastering' township laws - but rather strive to interpret the actual writings of the transcripts as linked to Lödöse in itself, to see if this can be deemed a logical interpretation. In the following sections, these arguments are discussed.

- Geographical names significant for Stockholm today.

- Trading rules for ships coming to the Lödöse harbor.

- Magnus Erikssons town law, section R 12:1, which adds to chapter 13 `the same law prevails for all towns within our country'.

Kungshamn and Åsön

- "§2. Alla de brott som begås mellan Lödöse och Konungshamn, [eller] i Konungshamn, de skola alla bötas efter Lödöse rätt. Alla de brott, som begås på Åsö, de skola också bötas efter stadens rätt. Bliva män skyldiga till brott i andra länder och andra städer, blir det icke förlikt förr än de komma till Konungshamn, då skall det allt bötas efter stadens rätt."23

Translation: Crimes commited between Lödöse and Kings harbor, [or] in Kings harbor, shall be fined according to the law of Lödöse. All crimes commited at Åsö, also shall be fined according to the law of the town. If men are found guilty of crimes commited in other countries and other towns, this will not be verdicted until they arrive in the Kings harbor, when they are fined according to the law of the town.

However, the original text named these places as Lythosä, Konungxhampn, and Ase:

- "Alla da sakir sum brytäs mellum Lydosä oc Konungxhampn, [äller] i Konungxhampn, de skulu allär bötäs äptir Lödosä rät. Allär de sakir där brytäs a Ase, da bötäs och äptir stadsins rät."24

Here, as in the above translation, the addition [eller] (or) is inserted by the translators, according to the master translation made by Schlyter in [Ref.107]. Notably, Gunnar Bolin25 wants to add the same sentence as in the later passage;

- "... mellan Lödöse och Konungshamn, [blir det icke förlikt förrän de komma till] Konungshamn."

This addition, ...this will not be verdicted until they arrive in..., do seem more adequate and conformistic, according to this author, although when viewing the complete chapter according to the following, the interpretation of Holmbäck and Wessén does come out as the most probable.

However, regardless of which interpretation is chosen, this passage does not change the geographical interpretation of the paragraph.

Following, each of the geographical arguments in favor of Stockholm as the origin for Lödöse `Bjärköarätt' of Holmbäck and Wessén are discussed, as (1) Konungxhampn, (2) Ase.

- Needed to reference the exact text of this passage, numbered R 12:1 for comparison; does the new law specifically mention Stockholm? If so, it might still be a general law - possibly older than the town itself - locally adapted but actively in use in all towns of the country, but by Magnus Eriksson declared from his capital Stockholm.

`Konungshamn' might mean any harbor under the kings control, within the jurisdiction of this town - in the case of Lödöse, we can only find two: the ancient harbor town Kongahälla to the south[Note23] and a harbor in a coastal village named Kungshamn on the west coast of Bohuslän[Note24].

This held in mind, the most likely interpretaion of `Konungxhampn' for Lödöse according to this author - though not preserved into our days as a distinct geographical location within Lödöse - is rather that it simply refers to the harbor of the town in question. Since the town is held as being under the kings control, so would its harbor seem natural to refer to as "the kings harbor". This, then would be the case for all trade center towns from the same time; the term `Konungxhampn' is likely to refer to the harbor per se found within any middle age trade center or town.

The second closely located geographical location named Kungshamn on the west coast of modern Sweden, is located opposite the old Norwegian trade center Kaupang. It is not likely that neither Kongahälla nor Kungshamn is related to Lödöse as jurisdictional references, but the existence of the modern town Kungshamn may well indicate an older existence of a matching harbor to Kaupang, in tradtion resembling the here suggested usage in ancient Sweden. Kungshamn, then, is likely to be the remains of a middle age village - probably a trade center in itself - for which the name of the town in this case the harbor name has become predominant and prevailing.

From an investigation on the geographical name, documented at Kungshamn etc., on page 187, we find a village or harbor named either Kungshamn or Konungshamn outside all the coastals Karlskrona, Oskarshamn, Västervik, Båstad, Nyköping, Valdermarsvik and Lödöse - that is, seven occurences besides the one outside Stockholm26. Also outside Lidköping (by Vänern; in essence a coastal town too) and Uppsala, in the province of Uppland, a geographical location named Kungshamn is found. Several of these towns have a history similar in age to that of Stockholm.

For Lödöse itself, the town is formed around the two (out of which only one remains) arms of the small river Gårdaån, in the middle ages known as Ljuda. The ancient harbor was located outside the castle, and outside the town itself. From the harbor and up to the town proper, there where a built-up area of diverse set of sheds, storehouses and other buildings. According to current excavation findings, the interpretation by this author of Lödöse with a harbor named as `Konungxhampn' is not at all unlikely, though of course no remaining geographical location has prevailed.27 This, though, is not so remarkable since the town itself lost its importance when Nya Lödöse was established to overcome the inferments by Norwegians at the mouth of river Nordre älv, from Kongahälla.

Hence, the reference in `Bjärköarätt', chapter 13, to `Konungxhampn' is probable to mean the coastal harbor of the trade town in question. Thus, there is no obvious connection exclusively made to the town Stockholm.

An investigation on the term `Ase' is presented in Ås och Ase, on page 111. From SAOB [Ref.70] the phrase `under sotkum Ase' is found, referrring to an ancient swedish expression meaning `under the roof of a building'. It is known from the viking era, and hence it is not an unlikely interpretation to view the expression `a Ase' in chapter 13 to mean inside anyones house within the towns jurisdictional area - a part from the houses in the town proper. In fact, the implicit phrase made in the original text supports this view (given above).

We thus may read `All crimes commited between the town and its royal harbor, or in the royal harbor [and] the crimes commited in anyones house within this jurisdiction' - all these crimes will be sentenced according to the towns law. That is, within the jurisdictional area that binds the territory to the town and not to the surrounding province or district.

This interpretation of `a Ase' gives us a completely logical intention in the paragraph, regardless of which town the law is written for. The text actually becomes generic.

A second possibility is to take the translation by Holmbäck and Wessén literally, choosing to translate `Ase' as ridge (ås). This, too, would fit very well as a description for Lödöse, interpreted as ` crimes commited between the ridges'.

- What is the original ancient Nordic meaning of Ase, does there exist any other confirmations on the expression `a Ase' such as the one given here?

- What connects Ase to an island Åsön according to the authors Holmbäck and Wessén, and specifically to the island where todays Södermalm in Stockholm is supposed to be located?

- From what time are the geographical names near Stockholm known?

Hence, the meaning of `a Ase' in chapter 13 of `Bjärköarätt' is at least ambigious and not clearly referring a geographical location outside Stockholm.

North and south `Malmen'

- "Den som rövar på Norra malmen eller Södra malmen och blir lagligen förvunnen därtill med sex vittnen..."28

The original text however states "a nyrri malmi äller sydrä"29. According to SAOB [Ref.70], the word `malm' is a general word not exclusively connected to the modern day geographical areas of Stockholm, known as Norrmalm and Södermalm. This is referenced in Malm, on page 114, from SAOB in the meaning I.2.a. From this it is clear that the text north or south `malm' might refer to any thickly wooded, upland areas outside any middleage (or older) villages or towns. It is simply common land, belonging to the village or town.

This gives us the following translation:

- The one that robs on the north or south upland forestal areas outside the town [... will be sentenced according to the town law].

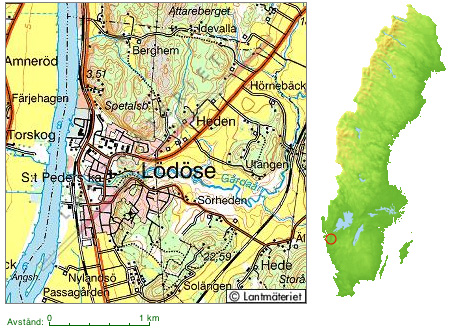

Thus, any town having such areas to the north and south might fit the description - as does, indeed, Lödöse itself, being located on the eastern shores of river Göta älv. From Lantmäteriet [Ref.94], the following map extract is given, see figure 1 on page 81. Green areas with brown lines represent wooden hillsides, each thicker brown line indicating another twenty-five metres.

The interpretation of `malm' as town districts in Stockholm is perhaps the most widely known today, but far from unique and, at any rate, certainly not predominant enough to make exclusive connections from the `Bjärköarätt' in B58 mentioning of such township parts in the 14th century. Furthermore, if the text was to have been a copy of a Stockholm version, it could be argued that it ought also to mention the eastern `malm', Östermalm.

The geographical directions, (only) north and south, is also found in other passages of the `Bjärköarätt' e.g. chapter 8, refering to `places where houses have been built'. If this passage was to have been copied from a Stockholm original, it is likely that the directions north and south would not have been enough to limit the extent of the jurisdictional area.

Hence, we may deem it probable that the reference of north and south `malm' in the Lödöse `Bjärköarätt' is rightfully written specifically for Lödöse and not for any other town, thus not being a copy of a `Stockholm master law'.

Trading rules for ships coming to the harbor

In chapter 8, Lödöse is mentioned - though here it is not commented by Holmbäck and Wessén as replacing Stockholm.

- "Den som kommer med skepp i hamn, [...] skall göra det kunnigt för fogden [...] inom tre dagar. Fogden skall hjälpa honom och bistå honom. Förr får han intet sälja.

§1. Den som köper något i ett skepp, större eller mindre, utom säd och säl, [blir bötfälld] Dock lovas Lödöse-fararna att sälja sill och lin i sina skepp och dock på det villkor, att de först föra alla sina andra varor in till lands.

§2. Den som stiger i en annans båt och köper något i den [får böta].

§3. Vidare får man allmänt köpa, så länge handeln varar, det är från pingst och till Mårtensmässan, överallt mellan de yttersta platser, som staden har bebyggt från söder och till norr."When a ship comes to harbor, the assistance of the local bailiff (fogde) must be awaited before any sales are allowed. [...] §1 Apart from seal fat (and/or train oil30) and grain, nothing may be bought onboard a ship or the buyer will be fined. But, the Lödöse-travellers may sell herring and flax (or possibly linen31) from their ships, provided that they first bring ashore all other goods. §2 If a man steps in any other boat and buys anything, he is fined. §3 Trade is allowed between Whitsun and Martinmas, in all built-up areas of the town from the south to the north.

The term used is Lödöse travellers, for which a discussion is held by Holmbäck and Wessén as to whether it pertains to (any) travellers coming to Lödöse, or travellers with origin in Lödöse (as opposed to travellers from other towns). They present the views of Schlyter ([Ref.107]) and Bolin32 that this existence can be taken as a grant for the existence of the paragraph in the alleged master `Bjärköarätt' for Stockholm - giving tradesmen from Lödöse special privilegies over other tradesmen in Stockholm. Another view presented is held by Ahnlund33, who claims that the orginal text (from the Stockholm master) should be Hälsinge-travellers, that is traders from the province of Hälsningland.

The referment to Lödöse-travellers demands text interpretation to be done differently depending on the direction chosen.

- If it refers to all traders coming to Lödöse, it can either be deemed unnescessary (not contributing to the writing of the paragraph since it pertains to all tradesmen) or as to indicate a difference for Lödöse compared to a more general master writing known for other, possible all other, trade centers; in Lödöse (but nowhere else if not specifically noted) the traders are also allowed to sell herring and flax without first bringing it ashore.

- If it refers to traders whose origin is Lödöse, the text must be interpreted as special privilegies for the local tradesmen, as opposed to other tradesmen. Then, also, the third paragraph is meaningful; if a buyer gets in a boat of trademen not from Lödöse and buys anything but seal and grain, he will be fined.

An interpretation of generalization

In the opinion of this author, the last sentence of the paragraph §13:2 clearly states that it is a general paragraph, valid not only in Stockholm but in all towns under the control of the `Bjärköarätt':

- If men have commited crimes abroad and in other towns, it shall be verdicted according to the [nearest] towns law, when these men arrives in [any] harbor of the king serving as harbor for that nearby town.

Otherwise, following the interpretation that the law refers to a specific `Konungxhampn' such as the one outside Stockholm, we have to deem any crime commited anywhere abroad to be verdicted in accordance to a towns law only when - or rather if - they come to "the one and only existing" `Konungxhampn' outside Stockholm.

It seems most unlogical to define in every specific trade town a jurisdiction linked to one single harbor, located on the east coast of Sweden. A more logical interpretation is to assume that every town - located near a significant coast or sea anywhere in Scandinavia34 - to define a limited jurisdictional area as within reach of its own royal harbor:

When a man found to have commited a crime abroad comes to a royal harbor, or to the trade town itself, he will be sentenced according to the law of this town.

In the case of B58, the town is of course Lödöse. Since we have fragments found of other town laws named `Bjärköarätt' we can rightfully assume that a crime commited anywhere abroad would be sentenced in whichever town is first reached when returning to Swedish territories, or when reaching the kings harbor of that town. When Magnus Erikssons town law, section R 12:1, adds to chapter 13:2 `the same law prevails for all towns within our country' it is logical. Here. it is written for the capital, to be valid for all other towns in the country. This can not be taken as a foundation for deeming the Lödöse version to be a copy of an older Stockholm master. It may well be a copy of a master, or rather a commonly known and spread law, but there are no indications that exclusively points to Stockholm for such a master. In the opinion of this author, all the arguments rasied in favour of Stockholm must be reconsidered in the light of the other objections rasied here; since the foundations used by Holmbäck and Wessén and their predescessors cannot be seen as unambigious, neither can later conclusions and interpretations they make in favour of Stockholm as the original master town law.

Seemingly, several of the middle age towns have had a nearby harbor named `Konungxhampn', or Kungshamn in modern day Swedish (compare point 1 above).

Hence, we find that the interpretation by Holmbäck and Wessén for `Konungxhampn' to refer to the geographical location outside Stockholm must be deferred as not logical, instead advocating the belief that the Lödöse transcript indeed may have been written to serve locally.

Summary of questioning of `Bjärköarätt' master origin

In conclusion, the foundations for assuming that B58 containing the Lödöse version of `Björköarätt' from around 1350 AD should be a direct transcript of the Stockholm version is clearly ambigious. [TBD, clearification and extended investigation needed on the unclear meaning of the term `a Ase' in paragraph 13:2]

Hence, an alternative origin to the area of Stockholm is not unprobable. Following this, in fact Magnus Erikssons town law might have been a construction based upon an older township law from another town rather than the opposite.

(Return to content list.)

Notes on establishing a common understanding of `Birka'

Notes on the meaning of `Birka'

It is interesting here to note that many ancient myths and sagas describes the rules held at markets, where vikings held the peace at the trading center for as long as it was ruled, but afterwards - whilst returning from a well deducted trade session - did not hesitate to attack and rob the neighbouring farmers, possible of goods and gold or silver that was partaken during the market35.

Notes on the term `Bjärköarätt'

A few remarks is raised here by this author upon the connection made to Stockholm for the Lödöse town law of B58, as discussed in Discussion on a common understanding of `Birka', on page 77.

Summarizing, there might be reason to believe that the law is actually in its origin older than the age of the town Stockholm; whereas there has certainly existed a similar law for Stockholm - as also, most probably, for all middle age (and older) trade centers or towns - it might be adequate to question some of the foundations for interpreting the Lödöse transcript as a copy of an older `Bjärköarätt' for Stockholm, such as it is referenced and concluded by Holmbäck and Wessén.

It is more probable, according to this author, that the Lödöse transcript is indeed written specifically for Lödöse. Similarities to other indications of written laws should rather be interpreted as using the same commonly known laws spread all over ancient Scandinavia (or even northern Europe).

This author finds the explanation of Björkön, Mälaren, to form the original version of a common Nordic law for trade centers, a wee bit farfetched. It is discussed in Questioning the origin for the term `Bjärköarätt', on page 77.

Thus, the oldest Norwegian transcript is made more than a 100 years prior to the Lödöse version, and likely prior to the foundation of the town Stockholm.

(Return to content list.)

Notes on questioning Stockholm as the master for Lödöse `Bjärköarätt'

The most apparent candidate for prevailing geographical location matching `Konugxhampn' would be the town Kongahälla, found not far away some distance south of Lödöse, just at the crossing of rivers Nordre älv and the lower part of Göta älv. Notably, the circumstances of nationality for Lödöse and the surrounding territories are not all clear from the early middle ages; generally the province of Bohuslän is considered as Norwegian whilst the valley along Göta älv was Swedish.

However, whereas Lödöse is clearly a middle age trade center linked to ancient Sweden, the same can not be said about Kongahälla - though it is known from about the same period in time. It is located on the Nordre älv river arm, apparently within Norwegian territories. The advantage for Lödöse is its location at the gate of the vast agricultural landscape in Västergötland, and as the northern limit we have the great waterfalls that, in ancient times, were an obstacle for seafaring up or down Göta älv to or from the lake Vänern. Kongahälla does not hold any such features that advocates the reputation of a trade center, a fact that might indicate an early linkage as the harbor of some larger trade center such as Lödöse. This though would imply cargo transfers and transports from Kongahälla to Lödöse, which is not a likely scenario. For this to be trustworthy, either the river Göta älv would have had to be considered unpassable for the larger boats used in seafaring trade activities, or the harbor Kongahälla should be located on the same riverside as Lödöse, which neither is the case.

Accidentally, an old meaning of the latter part, `hälla', is `to hold', that is possibly `held by the king' or `the place where the king was held'[Note25]. It definately had a harbor in the early middle ages, strategically located to control both river arms. As such it might be interesting to view Kongahälla as a controlling point for the administrative forces, wanting to gain control over the trade along these two rivers - which, in fact, was the reason for a later movement of Lödöse into Nya Lödöse at the mouth of Säveån near todays city of Göteborg when the Norwegian authorities claimed the right to take up toll for trading ships destined to Lödöse36.

Located at the northwest of Lödöse, Kungshamn on the west coast of the province Bohuslän is facing the Norwegian Oslofjord. Therefore, this harbor town is no doubt geographically too distant to come in question - if not as a similar counterpart of the Norwegian trading centre of Kaupang in Vestfold.

This investigation has not (yet) concerned the other Scandinavian trading centres in connection with `Bjärköarätt', and neither whether there exists similar references to geographical locations that would rule out an unambigious linkage to Stockholm.

Compare the history of Olav the holy as told by Snorri, [Ref.50], who in vain waited in Kongahälla for his bride to be, Ingegerd Olofs daughter. The accompanying fleet stayed in Kongahälla - this was the harbor.

In later centuries, when Kongahälla was provenly Norwegian, this location became important as the customs duty control, leading to the 15th century establishment of a new settlement for Swedish trade around the modern city of Gothenburg.

(Return to content list.)

Discussion summary

As stated in the above sections, there exist several accounts not only for actual locations, but also ethymologies for the term `Birka' that suggests that the location at Björkön is not the exclusively associated trading center named Birka.

Examination of the meaning of the name Birka shows that it is a valid assumption to hold the term Birka as secondary to the known law of trade, `Bjärköarätt', thus making it probable that different locations might have been referred to as `Birka', locally in different parts of Scandinavia and most importantly in different times.

Geographically, the trading center at Björkön is one amongst many, although by far the most thoroughly examined and excavated. Several locations known to have been ancient trade centers have had the same connection to trade and the name `Bjärköarätt' as the town Birka on Björkön.

It is therefore possible to consider the references to Birka being located at Björkön, both in the days of Ansgar and as known and referred to in the 10th and 11th centuries, as being ambigous. It is possible that a direction given in the neighborhood of Sigtuna, Uppland, in the 11th century for `Birca'37 is given to the nearest located trading center - especially if, as likely is the case - there are no (longer, or ever existed, any) memorizes of a missionary seen at that trade center a couple of hundred years earlier.

We can thus undertake the task of localizing Ansgars Birka objectively, and without being pre-determined to localize it at Björkön.

(Return to content list.)

Placing Ansgars Birka in ancient Sweden

From the descriptions made by Adam of Bremen and Rimbert of the town Birka that the holy Ansgar travels to in the 830s, there is not much to fit the description of Birka at Björkön, Mälaren.

On the other hand, the ancient remains at Köpingsvik, Öland, fits very well to this description.

(Return to content list.)

The Birka of Ansgar

The time aspect in Adams different accounts of Birka

At the time when Ansgar travels to Birka, the references given are not the same as when Adam later, in what appear to be the account of his oral sources, describe the trading place that is located near the town Sigtuna. I quote Tore Nyberg38:

- "Problemen med Birkas lokalisering är utan tvivel en följd av att två traditionslinjer bryts: dels Birka som mål för Ansgar och hans medhjälpares sjöfärder och senare Unnis försök att återfinna Ansgars Birka; dels de nya upplysningarna om Birka på 1000-talet, som nått Adam både via inlandsvägen över Skara och Telje och via kustvägen från Birka och Sigtuna."

To locate Birka, we have to make a difference between the geographical references from the days of Ansgar, and to the references made in the 11th century when travelling was made both via Skara/Telje, and along the coastline to the trading center Birka near Sigtuna.

(Return to content list.)

Geographical references to the Birka of Ansgar

[This article is yet only at a preliminar status; therefore a complete set of references have not been entered at this time.]

When Ansgars visit to Birka is referenced, Adam relies mostly on Vita Ansgari, written by his successor Rimbert [Ref.68].

(Return to content list.)

The travelling of Ansgar

The first account of Birka here is when Ansgar arrives there on the request by the Sueonic king Björn39, travelling from the king of Danes, Harald Klak40:

- "With great difficulty they accomplished their long journey on foot, traversing also the intervening seas, where it was possible, by ship, and eventually arrived at the Swedish port called Birka."

It is notable that no references are made to places, towns or people being passed during this travelling[Note26].

The travelling of Unni, 935 AD

The first geographical reference by Adam is when archbishop Unni travels to Birka, stated as 70 years after Ansgar41. In this reference by Adam, it is stated that Birka is a town of the Götar, located in the midst of Sueonic territory, not far from their celebrated cult place Ubsola. Quotes from latin version, [Ref.57]:

- "Birca est oppidum Gothorum, in medio Suevoniae positum , non longe ab eo templo, quod celeberrimum Sueones habent in cultu deorum, Ubsola dicto"

Furthermore, the location is said to be within a bay, facing the north into the Baltic Sea41[Note27]. To set an obstacle for enemies, the bay is said to be blocked by rocks to a distance of 1000 stadies, i.e. about 16 km (1 stadie = 160-180 m):

(Return to content list.)

Discussion on placing the Birka of Ansgar in ancient Sweden

It is held by this author that the above listed references can be used as a foundation for making a geograhically based localization of Ansgars Birka to Köpingsvik, province of Öland, Sweden.

Ansgars Birka at Björkön

The circumstances given for Birka can never be applied to Birka at Björkön.

- It can not be called a Götisk town according to the Svealand theory - and it is hardly located in the midst of Sueonic territory.

- It is not located in the Baltic Sea.

- The bay outside of Björkön is at most 2 km.

- There are no blockings in or just underneath sea level, as of 1000 AD.

Ansgars Birka at Köpingsvik

They may however adequately be applied to a Birka in Köpingsvik.

- It can be deemed a Götisk town, since the eastmost Götars are assumed to be living along the eastern shores of the Baltic Sea, and also the island habitants of Gotland lies further to the east.

- It is located in a bay to the north (the Kalmar strait of today was not as broad around 1000 AD - at Stora Rör just to the north of Kalmar, it was practically closed for sailing. To visitors from the north, the strait must have seemed to be a closed bay.

- The width of the strait just north of Köpingsvik is right about 16 km, from the main land to the island Öland. Also, from the corner of the inner bay surrounding Köpingsvik, the width from Borgholm to the northeast (coastline right to the north of Köpingsvik) is also right about 16 km.

- Some 25 km north of Köpingsvik, the islands and skerries from the mainland streches about 10 km eastwards, at the small island Dämman, making up a seemingly hidden obstacle of rocks over or just underneath the surface - making the sailing free width here rather 5 km than 16 km.

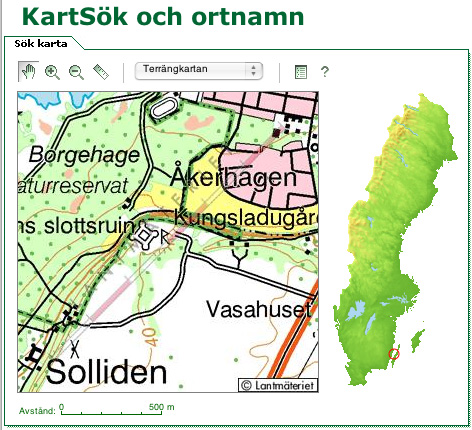

- Close to Köpingsvik we have the ancient castle Borgholm, for which additional myths of interest may be referred, e.g. of the ancient well inside the castle42. Even more so interesting is the geographical surroundings of Borgholm, see figure 2 on page 90.

Figure 2. Borgholms slott, province of Öland, near Köpingsvik. Provided from Lantmäteriet, [Ref.94].

- Compare [Note56] in article [Ref.7], A commented summary of Adam of Bremen, Discussion on Book IV, on page 173.

Notes on placing Ansgars Birka

Notes on geographical references to the Birka of Ansgar

A likely scenario for such a journey would be to traverse Scania and then hither by boat, across Hanöbukten. If the goal was located in lake Mälaren, the alternative route would have been through western Sweden rather than through the province of Småland (Finnveden, Värend). If the goal was at the island Öland, the same route eastwards from Dania along the eastern shores of modern Sweden would be followed as for travelling to Mälaren through the Baltic Sea.

In [Ref.11], Nyberg suggests that the cardinal compass points of north and east must be compensated when referencing Adams description of the Sueonic territorries. He deducts that `east' should be interpreted as `'north'43, which makes sense for the description in book IV-25 and corresponds well to the idea of Ansgars Birka being located at Björkön.

However, this author considers Nybergs theory as inconsequent, since that view applied to book I-60, where the bay outside Birka is said to stretch to the north into the Baltic Sea, will give a complete opposite result compared to the intentions of changing the directions made by Adam.

Thus, given the water level around the mid 11th century, the lake Mälaren of today may well have been apprehended as a bay into the Baltic Sea. It does, however, stretch to the east. Following Nybergs interpretation, Adam has intended for the bay to strech west into the Baltic Sea, which not even in good will can be the case.

Most importantly, as discussed above, the bay outside the island itself is not nearly as large as Adams says it should be - although it does face the north.

(Return to content list.)

TBD

Further analysis

(Return to content list.)

Conclusions

[This article is yet only at a preliminar status; therefore the complete conslusions cannot be entered at this time.]

The geographical location of Birka

No certain conclusions can be made without further archeological examination of the sites of interest. But, from my reading there are several indications that may serve as a basis for re-evaluation of the stated conclusion that the trading center at Björkön was not the town called Birka that Ansgar came to in the 830s.

Rather, there are much indicies that may be set as a claim for investigating Köpingsvik, Öland, which seem to have a lot more to offer than Birka at Björkön, in terms of making a coherent reading out of Adams recapitulation of the mission brought to the Nordic territories by the archbishopery Hamburg-Bremen.

From the findings in this article, it seems plausible to consider Köpingsvik as a prime candidate for localizing the Birka of Ansgar. This, then, assumes that the known references of Birka in ancient time can be seen as different geographical locations.

It is the hope of this author that, in the near future, extensive excavations could be initiated so as to verify any possible remains making it possible to draw distinctive conclusions on whether Köpingsvik is likely to resemble the trade center Birka that Ansgar visited in the mid 9th century.

(Return to content list.)

Article references

Litterature and background articles

Background articles

- Summaries of selected litterature

- A commented summary of Adam of Bremen

- Modern places aligned with named ancient locations

Litterature

- See Litterature references for a list of litterature references

(given in swedish).- See Terminology for a definitions list of used terminology.

(Return to content list.)

External links

Article revision history

(Return to content list.)

(Return to top of page.)

(Return to main article.)

(Return to home page.)

3Historically, stemming from the 19th century, these theories have been referred to as 'Västgötaskolan', the school of Västergötland orgins for ancient Sweden.

6More specifically, Hamburg-Bremen was an ordinary bishop seat serving under Köln, representing the lands of Northalbings, but held arch bishop claims for the Nordic terrritories. See Janson in [Ref. 59] and Hallencreutz in [Ref. 11].

7The term barbarian is, as shown by Lund in [Ref. 12], the commonly used classical reference to all tribes not incorporated in the Roman empire. Through the middle ages following an up until Adams days, the term became a synonym for heathen people, and it can be argued that Adam has referenced the Nordic people according to both the classical and the middle age usage of the term.

11Possibly, the sueones were a collectively used name for all tribes just in the same way as `Nortmannir' was used to describe the inhabitants of Norway.

12Compare BIRKA, on page 73, where SAOB, [Ref. 70], makes the same connection. Possibly Schlyter have referenced this source too.

13The word part `ö', meaning island, is not nescessarily to be translated as island. An alternative interpretation is that of a secluded area within a larger land area.

17From Schück, [Ref. 108], Holmbäck and Wessén, presents the sentence (lat.) `Saxo advocatus ac communitas ciuium de Stokholm' and `jure ciuili ac legum terre', interpreted as supportive. See [Ref. 56-2], Inledning, VI. Om Bjärköarätten, p. XCVI.

18Holmbäck and Wessén holds that the `byärkerätt' referenced by Magnus Eriksson for the new town law of Jönköping must be his newly defined town law, since at the same time the king revokes `the older law in use in Jönköping' in favor of the new one. See [Ref. 56-2], Inledning, VI. Om Bjärköarätten, p. CI.

22`Söderköpingsrätten' is only known in fragmentary notes by Johannes Bureus (d. 1652). The Visby law is known in a german transcript from around 1350 AD. See Holmbäck and Wessén, [Ref. 56-2], Inledning, VI. Om Bjärköarätten, p. C f.

25According to note 8 of chapter 13, [Ref. 56], presented by Gunnar Bolin, Gunnar Bolin in Stockholms uppkomst, 1933, p. 296f.

30Train oil is added by Holmbäck and Wessén to broaden the meaning of `seal' in the paragraph, see note 3 of chapter 8, [Ref. 56], p. 475.

32According to note 4 of chapter 8, [Ref. 56], p. 475 presented by Gunnar Bolin in Stockholms uppkomst, 1933, p. 296f.

33According to note 4 of chapter 8, [Ref. 56], p. 475 presented by Nils Ahnlund in (Sv)HT 1927, p. 452 note 2.

34Assuming the `Bjärköarätt' in its different existences all over Scandinavia to have the same original intentions, we must allow not only Swedish towns to bear this linkage.

37When bishop Adalvard travels to Sigtuna in the mid 11th century, he makes a stop at a (then) totally ruined trade center. Adaldvard and his companions travelled via Skara and the province of Västergötland. See [Ref. 11], book IV-30 and Scholie 142.

41Adam of Bremen, [Ref. 11]; Book I, ch. 60, p. 60. In [Ref. 57], the same passage is given as Book I, ch. 62.

42In Gåtfulla platser, [Ref. 81], p. 36f., Linell tells of a tale concerning the "virgin well" in the northern tower of the castle, connected to the witches of the island Blå Jungfrun.

43See Nyberg, Tore; Stad, skrift och stift, [Ref. 11], p. 317. Also see the article A commented summary of Adam of Bremen, Discussion on Book IV, on page 173.

|

http://www.wilmer-t.net wilmer.t@comhem.se |